Hello, I’m Hong Minhee, Libplanet committer at Planetarium. In this post, I want to talk about why we came to a conclusion to run unit tests on Unity too, the most widely used game engine, and how we actually approached it.

Supporting Different Environments on Libplanet

Libplanet is a common library that solves game implementation problems such as P2P communication and data synchronization when creating online multiplayer games that run on distributed P2P.

Automated tests, especially unit tests, are needed to achieve rapid improvement while minimizing malfunctions that are prone to regressions or corner cases. Furthermore, Libplanet is a library and because it is difficult to determine which operating system and .NET runtime each game or app will use, we need to run all tests in as many different environments as possible.

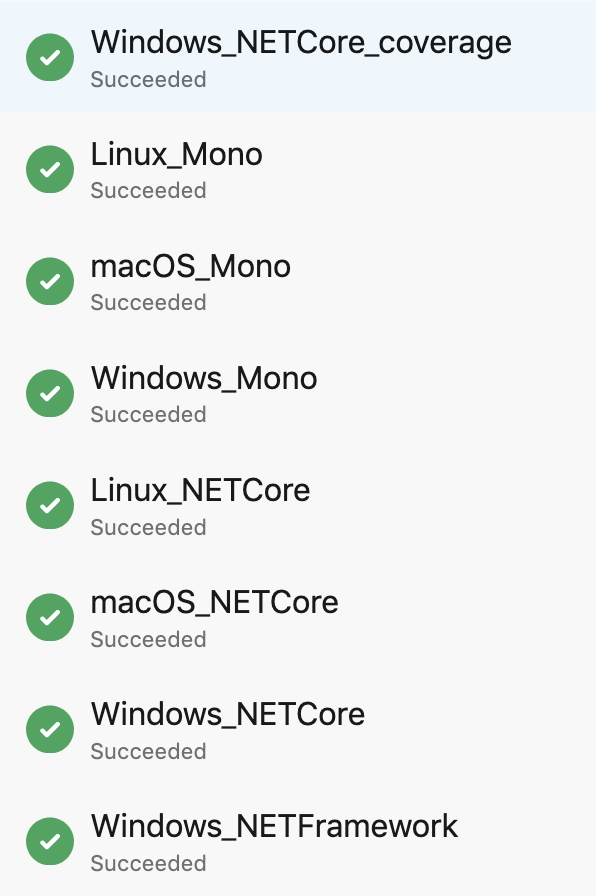

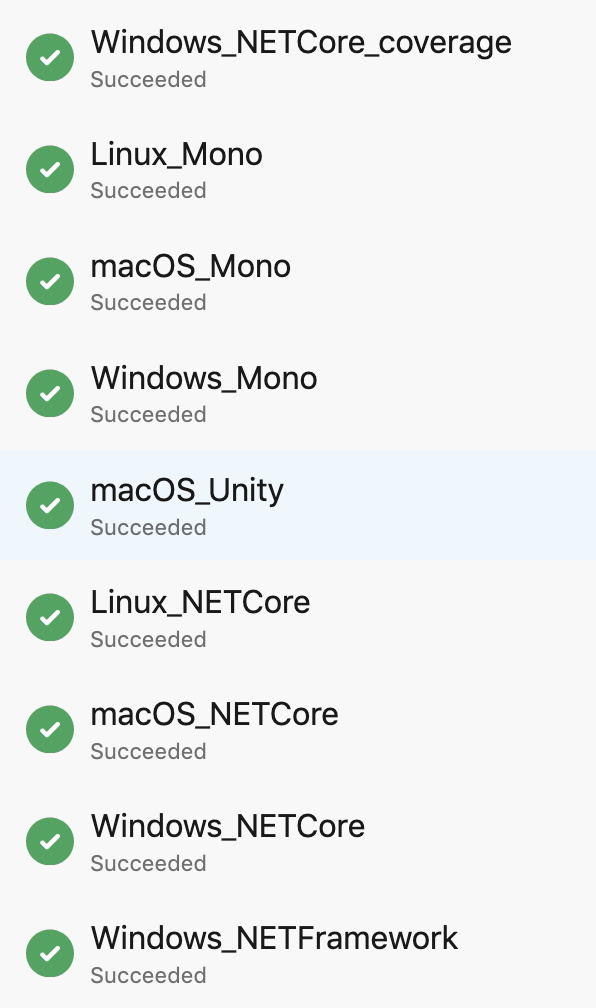

So our team had run tests on [Azure Pipelines]1 with (Linux, macOS, Windows) × (.NET Framework, Mono, .NET Core) combination2 whenever a push or a pull request was made in the Libplanet repository.

The combination of environments tested on each build

Unity ≠ Mono

At first, we thought this was enough because Unity uses Mono Runtime. But as we used Libplanet to develop our game on Unity, we had to encounter unexpected behaviors in the game several times, and it became increasingly evident that just passing the test on Mono was not enough.

In fact, the Mono used in Unity seems to be a fairly long-standing downstream, with a lot of patches added to the upstream. And even if they were tested at the exact same Mono runtime, there were a lot of special conditions created by Unity Player. For instance, NetMQ, ZeroMQ’s C# implementation, had numerous library malfunctions due to many complicated things happening inside compared to the simplicity of the APIs revealed on the outer layer.

All of these considerations led to an agreement that a testing environment for Unity needed to be added to CI to ensure reliable functionality.

Testing xUnit.net on Unity

Because there is a unit testing feature available in Unity, we tried to use it at first. Unfortunately, Unity’s unit testing was done in an Editor environment used by game developers, not in a Player environment, and the testing framework supported only NUnit. We thought about changing all of Libplanet’s xUnit.net-based test codes, to NUnit, but with such a high volume of codes to change at once, we didn’t want to risk making mistakes that are hard to notice.

So we decided to create a test runner app instead of a game app with Unity. Fortunately, xUnit.net was well divided between APIs for writing tests and APIs for running tests. This is probably due to the diverse frontend plug-ins to various IDE, GUI and CLI. In fact, if you search “xunit runner” on NuGet, you’ll get a xUnit.net test runner for a variety of environments.

A downside is that because there are no API documents, we had to search the source code of xUnit.net and the source code of other test runners.3

The test runner API on xUnit.net is roughly as follows: First, the client code looks for test classes and the tests

methods within those classes from the assembly files (.dll) passed through the input. After, the client code can

decide which test to run. Then, the test cases are run by the test runner. Because the test discovery and execution

can be done in parallel for performance, the API follows a typical IoC

pattern. An interface called IMessageSinkWithTypes, which receives events such as test

discovery, start running, failure, success, skip, and so on in the form of a message, must be implemented in the client

code to show the log on screen when such events occur. Because our team didn’t run the tests in parallel, it was quite

frustrating to have a less liberal API with a lengthy client code. 🙄

Building a CLI with Unity

Our greatest concern when creating a Unity test runner was that since this was to be done on CI in the first place, we believed that the test runner had to be manipulated by the CLI rather than by the graphics screen, and the results should be visible. So with Unity being a platform for making graphic games, we were worried whether it’d be a good idea or not to actually create a CLI app.

Fortunately, we found out that Unity has a headless mode, which means that all logs taken in

Debug.Log() method are output as standard output, without graphical display.

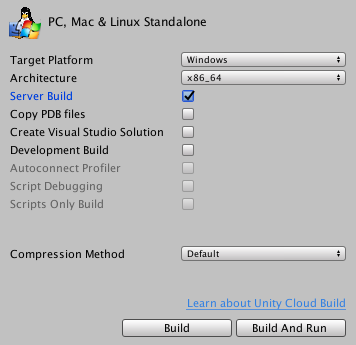

Server Build

option in Unity build settings that turn on headless mode

Even if you don’t use the Debug.Log() method provided by Unity, we’ve also figured out that just like creating a

typical application the Console class provided by the .NET standard works as well.

However, since the Main() method cannot be defined, the command line factor was not accepted as the string[] args

parameter of the Main() method, but instead had to be obtained as the Environment.GetCommandLineArgs()

method. Similarly, the program’s termination required an explicit call to the Application.Quit() method to

terminate the process directly.

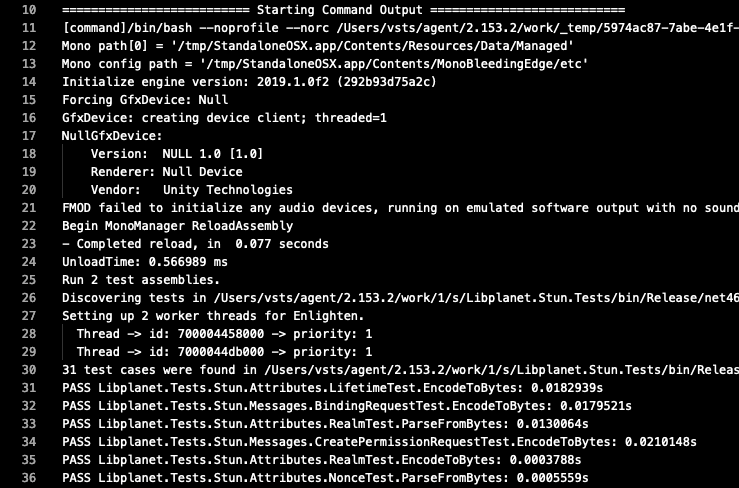

Lastly, there were messages being output from Unity player itself, but we couldn’t find a way to block it, so we had to wrap it up.4

Unity player’s own message, printed on the first and last line, was never removed.

Build Automation

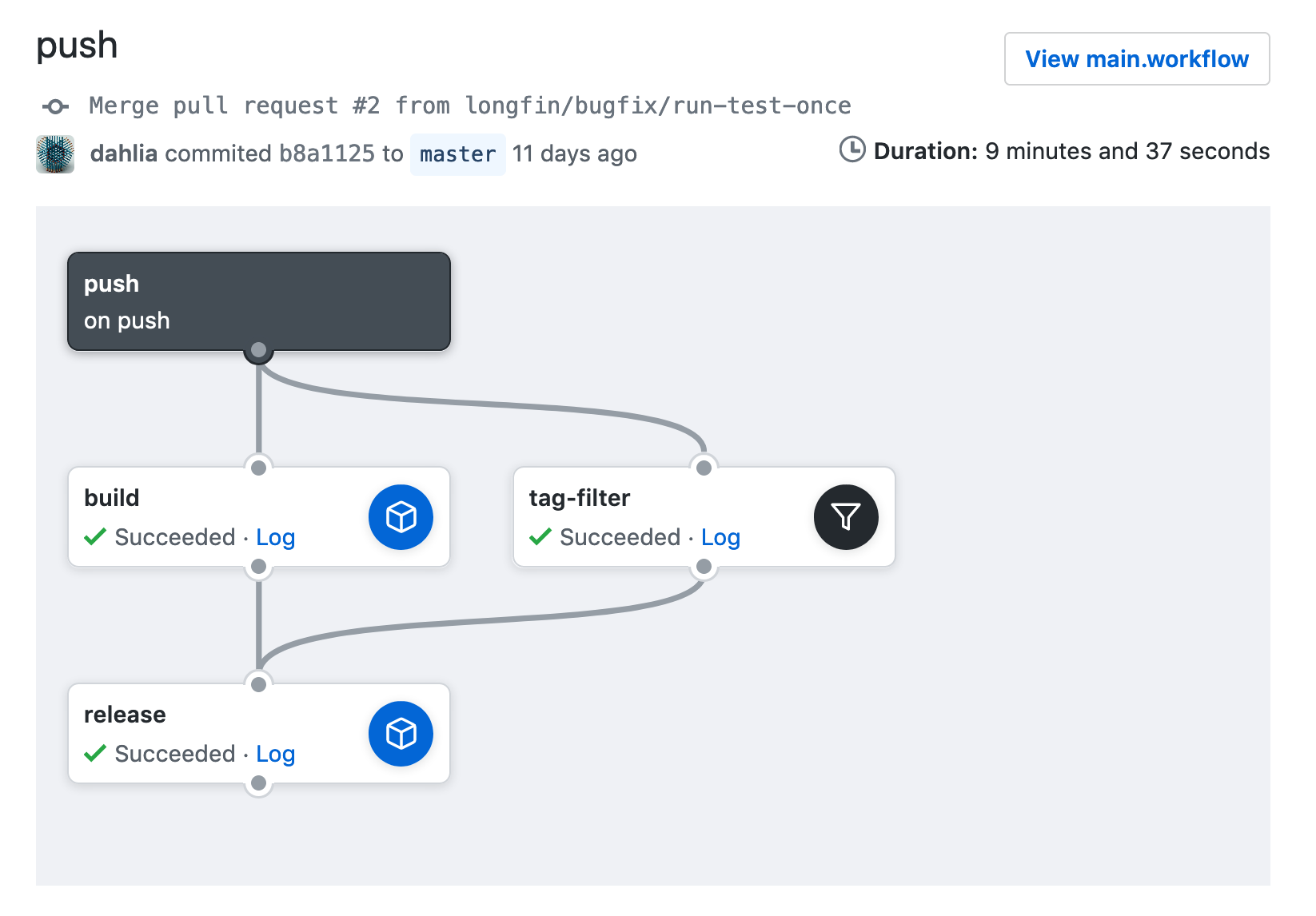

Building a CLI app with Unity and writing a document on how to build one on Windows as well as Linux or macOS makes the process tricky and easier for people to get inconsistent results. So we decided to make a tag in the repository and when pushed, and it’ll automatically build for Linux, macOS, and Windows.

Although we thought about putting CI on the board, we decided that it was unnecessary and used GitHub Actions to build it.

Referring to Kawai Yoshifumi’s post, we were able to carry out the entire build process inside the Docker. In the process, we experienced things that we hadn’t experienced in other environments:

Because Unity was a commercial product, we needed to activate the license.

Unity has somewhat an ambiguous boundary between an editor and a player. The code that will run in the editor environment can also be scripted, and this enables the app to be built by itself because Unity includes the app-building script as part of the app and then runs it.

At first, we thought we needed to build on all three operating systems, but fortunately, Unity supported cross-compiling and we were able to build the app for macOS and Windows on Linux.

Being Built on GitHub Actions

Conclusion

Current Build with Unit Test Added in Unity Environment

The newly built xUnit.net test runner for Unity has been applied on Libplanet project and is currently working well. By working well, we mean that the tests are often breaking due to different actions that are only seen in Unity environments. 😇 Of course, we’re glad to accept it because that’s the point of building a unit test — to find bugs as early as possible.

The runner is not yet neatly organized, but we have still put it up as an open source on GitHub. The executable file is available on the releases page, so if you want to try it out, it’s all yours!

As of June 2019, CI services that support all Linux, macOS, and Windows include Travis CI and Azure Pipelines. Our team used Travis CI at first, but it didn’t perform well, so we’re now using Azure Pipelines. ↩︎

Because the .NET Framework supports only Windows, it will be tested in 7 environments instead of 9. ↩︎

Because the .NET IDE has become very common for quite some time, there are many projects that don’t post API documents on the Web and simply leave XML document annotations in the source code. Those annotations will appear small as a tooltip when the class or method is automatically completed in IDE. ↩︎

If anyone knows how, please let us know. Or better, send us a pull request! ↩︎